The United States of America

Resolutions for Independence

A Brief History

"The Union is much older than the Constitution. It was formed, in fact, by the Articles of Association in 1774. It was matured and continued by the Declaration of Independence in 1776. It was further matured, and the faith of all the then thirteen States expressly plighted and engaged that it should be perpetual, by the Articles of Confederation in 1778. And finally, in 1787, one of the declared objects for ordaining and establishing the Constitution was 'to form a more perfect Union.' " -- Abraham Lincoln First Inaugural

Even President Abraham Lincoln missed the fact, in his first inaugural address, that there were two Resolutions passed by the Second Continental Congress declaring United States Independence. The first Resolution declaring U.S. Independence actually preceded the Declaration of Independence, which most U.S. Citizens know was passed on July 4th, 1776.

On June 7th, 1776 Virginia Delegate, Richard Henry Lee, brought before the Second Continental Congress of the United Colonies a "Resolution for Independency" for their consideration. The Journals of Congress report on June 7th, 1776:

Certain resolutions respecting independency being moved and seconded, Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

That it is expedient forthwith to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign Alliances.

That a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respective Colonies for their consideration and approbation.

On Saturday, June 8th, the "Resolution for Independency" derived primarily from the May 15, 1776 Resolves of the Virginia Convention was referred to a committee of the whole (the entire Continental Congress), and they spent most of that day as well as Monday, June 10th debating independence. The chief opposition for independence came mostly from Pennsylvania, New York and South Carolina. Thomas Jefferson reported that they "were not yet matured for falling from the parent stem." Since Congress could not agree more time was needed "to give an opportunity to the delegates from those colonies which had not yet given authority to adopt this decisive measure, to consult their constituents .. and in the meanwhile, that no time be lost, that a committee be appointed to prepare a declaration." [ii]

Resolved that it is the opinion of this Committee that the first Resolution be postponed to this day three weeks and that in the meantime a committee be appointed to prepare a Declaration to the effect of the said first resolution + least any time skid be lost in case the Congress agree to this resolution - Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses National Archives

Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent states, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the state of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved [i]

The Rhode Island Delegates summed up these events to in a letter Governor Nicholas Cooke:

The Grand Question of Independence was brought upon the Tapis the Eighth Instant, and after having been cooly discussed, the further Consideration thereof was on the 10th postponed for three Weeks, and in the mean Time, least any Time should be lost in Case the Congress should agree to the proposed Resolution of Independence, a Committee was appointed to prepare a Declaration to the Effect of said Resolution, another a Form of Confederation, and a Third a Plan for foreign Alliances.A Committee of Five was chosen with Thomas Jefferson of Virginia being picked unanimously as its first member. Congress also chose John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Robert R. Livingston, and Roger Sherman. The committee assigned Jefferson the task of producing a draft Declaration, as proposed in Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, for its consideration.

Mr. Jefferson had been now about a Year a Member of Congress, but had attended his Duty in the House but a very small part of the time and when there had never spoken in public: and during the whole Time I satt with him in Congress, I never heard him utter three Sentences together. The most of a Speech he ever made in my hearing was a gross insult on Religion, in one or two Sentences, for which I gave him immediately the Reprehension, which he richly merited. It will naturally be enquired, how it happened that he was appointed on a Committee of such importance. There were more reasons than one. Mr. Jefferson had the Reputation of a masterly Pen. He had been chosen a Delegate in Virginia, in consequence of a very handsome public Paper which he had written for the House of Burgesses, which had given him the Character of a fine Writer. Another reason was that Mr. Richard Henry Lee was not beloved by the most of his Colleagues from Virginia and Mr. Jefferson was sett up to rival and supplant him. This could be done only by the Pen, for Mr. Jefferson could stand no competition with him or any one else in Elocution and public debate. [iii]

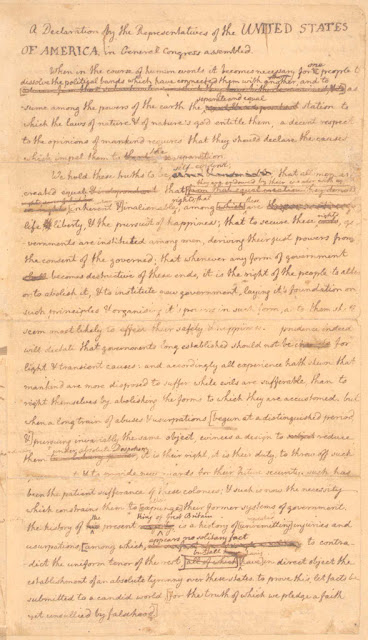

Jefferson's writing of the original draft took place in seventeen days between his appointment to the committee until the report of draft presented to Congress on June 28th. Thomas Jefferson drew heavily on George Mason's Virginia Declaration of Rights (passed on June 12, 1776), Common Sense, state and local calls for independence, and his own work on the Virginia Constitution.

Jefferson's original rough draft was first submitted to Benjamin Franklin and John Adams for their thoughts and changes. Jefferson wrote "… because they were the two members of whose judgments and amendments I wished most to have the benefit before presenting it to the Committee". [iv]

Jefferson's original rough draft was first submitted to Benjamin Franklin and John Adams for their thoughts and changes. Jefferson wrote "… because they were the two members of whose judgments and amendments I wished most to have the benefit before presenting it to the Committee". [iv]

Thomas Jefferson's DOI Draft

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Authenticate your Declaration of Independence Click Here

According to historian John C. Fitzpatrick the Declaration's

"... genesis roughly speaking, is the first three sections of George Mason's immortal composition (Virginia Declaration of Rights), Thomas Jefferson's Preamble to the Virginia Constitution, and Richard Henry Lee's resolution..."[v]

On June 29th a massive British fleet reached the entrance to the Hudson River. The British war fleet arrives in New York Harbor consisting of 30 battleships with 1200 cannon, 30,000 soldiers, 10,000 sailors, and 300 supply ships, under the command of General William Howe and his brother Admiral Lord Richard Howe.

Congress was called to order on July 1st at 9 am and they were made aware of the British Fleet's arrival in New York's Harbor. Serious debate consumed most of that hot and humid Monday. The following July 1st account is published in the Letters of the Delegates:

Congress was called to order on July 1st at 9 am and they were made aware of the British Fleet's arrival in New York's Harbor. Serious debate consumed most of that hot and humid Monday. The following July 1st account is published in the Letters of the Delegates:

On Monday the 1st of July the house resolved itself into a committee of the whole & resumed the consideration of the original motion made by the delegates of Virginia, which being again debated through the day, was carried in the affirmative by the votes of N. Hampshire, Connecticut, Massachusets, Rhode island, N. Jersey, Maryland, Virginia, N. Carolina, & Georgia.

South Carolina and Pennsylvania voted against it. Delaware having but two members present, they were divided. The delegates for New York declared they were for it themselves, & were assured their constituents were for it, but that their instructions having been drawn near a twelvemonth before, when reconciliation was still the general object, they were enjoined by them to do nothing which should impede that object. They therefore thought themselves not justifiable in voting on either side, and asked leave to withdraw from the question, which was given them.

The Committee rose & reported their resolution to the house. Mr. Rutlege of South Carolina then requested the determination might be put off to the next day, as he believed his collegues, tho' they disapproved of the resolution, would then join in it for the sake of unanimity. The ultimate question whether the house would agree to the resolution of the committee was accordingly postponed to the next day.On the morning of July 2, 1776 the New York Delegates wrote the newly elected Provincial Congress in NYC for instructions as the vote for independence was eminent.

Philadelphia 2d July 1776 - to the New York Provincial Congress

Gentleman,

The important Question of Indepency was agitated yesterday in a Committee of the whole Congress, and this Day will be finally determined in the House. We know the Line of our Conduct on this Occasion; we have your Instructions, and will faithfully pursue them. New Doubts and Difficulties however will arise should Independency be declared; and that it will not, we have not the least Reason to expect nor do we believe that (if any) more than one Colony (and the Delegates of that divided) will vote against the Question; every Colony (ours only excepted) having withdrawn their former Instructions, and either positively instructed their Delegates to vote for Independency; or concur in such Vote if they shall judge it expedient. What Part are we to act after this Event takes Place; every Act we join in may then be considered as in some Measure acceding to the Vote of Independency, and binding our Colony on that Score. Indeed many matters in this new Situation may turn up in which the Propriety of our voting may be very doubtful; tho we conceive (considering the critical Situation of Public Affairs and as they respect our Colony in particular invaded or soon likely to be by Powerful Armies in different Quarters) it is our Duty nay it is absolutely necessary that we shoud not only concur with but exert ourselves in forwarding our Military Operations. The immediate safety of the Colony calls for and will warrant us in this. Our Situation is singular and delicate No other Colony being similarly circumstanced with whom we can consult.

We wish therefore for your earliest Advice and Instructions whether we are to consider our Colony bound by the Vote of the Majority in Favour of Indepency and vote at large on such Questions as may arise in Consequence thereof or only concur in such Measures as may be absolutely necessary for the Common safety and defence of America exclusive of the Idea of Indepency. We fear it will be difficult to draw the Line; but once possessd of your Instructions we will use our best Endeavours to follow them.

We are with the greatest Respect your Most Obedt Servts.

Geo. Clinton.

John Alsop

Henry Wisner

Wm. Floyd

Fras. Lewis.The previous day, John Jay had written to Robert Livingston that the New York provincial Congress had adjourned:

I returned to this City from Elizt. Town, & to my great mortification am informed that our Convention influenced by one of Gouverneur Morris' vagrant Plans have adjourned to the White Plains to meet there tomorrow.

Consequently, on July 2nd, the New York Delegates unaware of the adjournment received no speedy reply. Their letter was held until the New York Provincial Congress reconvened in White Plains. Robert R. Livingston responded to John Jay's letter well after the vote for Independence as follows:

I have but a moments time to answer your letter. I am mortified at the removal of our convention. I think as you do on the subject. If my fears on account of your health would permit I shd. request you never to leave that volatile politician a moment. I have wished to be with you when I knew your situation. The Congress have done me the honour to refuse to let me go. I shall however apply again to day. I thank God I have been the happy means of falling on a expedient which will call out the whole militia of this country in a few days-tho' the Congress had lost hopes of it from the unhappy dispute & other causes with which I will acquaint you in a few days. We have desired a Genl to take the Command. I wish Mifflin may be sent for very obvious reasons. If you see [him] tell [him] so from me. I have much to say to you but [not a] moment to say it in. God be with you.

The Continental Congress had opened on July 2nd as planned with New York unable to vote. The Pennsylvania Delegation vote became 3 to 2 yes for independence because Robert Morris and John Dickinson, who voted no on July 1st, chose not to attend the July 2nd session. [vi]

Despite a second British Fleet arriving in Charleston, South Carolina's harbor on June 1st, 1776, Delegate Edward Rutledge urged his fellow delegates to vote for the resolution. Arthur Middleton, son of First Continental Congress President Henry Middleton, shucked his father's loyalist wishes and joined his fellow Delegates in changing the colony's position from a July 1st no to an unanimous yes for independence.

Finally Caesar Rodney, who was summoned by fellow delegate Thomas McKean, [vii] arrived suffering from a serious facial cancer and afflicted with asthma after riding 80 miles through the rain and a lightening storm. He broke Delaware's 1 to 1 deadlock by casting the third vote for independence.

All 12 colonies, except for New York whose delegates were not empowered to vote, adopted the July 2nd, 1776 Resolution for Independency.

Despite a second British Fleet arriving in Charleston, South Carolina's harbor on June 1st, 1776, Delegate Edward Rutledge urged his fellow delegates to vote for the resolution. Arthur Middleton, son of First Continental Congress President Henry Middleton, shucked his father's loyalist wishes and joined his fellow Delegates in changing the colony's position from a July 1st no to an unanimous yes for independence.

Finally Caesar Rodney, who was summoned by fellow delegate Thomas McKean, [vii] arrived suffering from a serious facial cancer and afflicted with asthma after riding 80 miles through the rain and a lightening storm. He broke Delaware's 1 to 1 deadlock by casting the third vote for independence.

All 12 colonies, except for New York whose delegates were not empowered to vote, adopted the July 2nd, 1776 Resolution for Independency.

|

| Resolution for Independency which was passed on July 2, 1776. |

“The Subject had been in Contemplation for more than a Year and frequent discussions had been had concerning it. At one time and another, all the Arguments for it and against it had been exhausted and were become familiar. I expected no more would be said in public but that the question would be put and decided. Mr. Dickinson however was determined to bear his Testimony against it with more formality. He had prepared himself apparently with great Labour and ardent Zeal, and in a Speech of great Length, and all his Eloquence, he combined together all that had before been written in Pamphlets and News papers and all that had from time to time been said in Congress by himself and others. He conducted the debate, not only with great Ingenuity and Eloquence, but with equal Politeness and Candour: and was answered in the same Spirit.No Member rose to answer him: and after waiting some in hopes that some one less obnoxious than myself, who was still had been all along for a Year before, and still was represented and believed to be the Author of all the Mischief, I determined to speak.

It has been said by some of our Historians, that I began by an Invocation to the God of Eloquence. This is a Misrepresentation. Nothing so puerile as this fell from me. I began by saying that this was the first time of my Life that I had ever wished for the Talents and Eloquence of the ancient Orators of Greece and Rome, for I was very sure that none of them ever had before him a question of more Importance to his Country and to the World. They would probably upon less Occasions than this have begun by solemn Invocations to their Divinities for Assistance but the Question before me appeared so simple, that I had confidence enough in the plain Understanding and common Sense that had been given me, to believe that I could answer to the Satisfaction of the House all the Arguments which had been produced, notwithstanding the Abilities which had been displayed and the Eloquence with which they had been enforced. Mr. Dickinson, some years afterwards published his Speech. I had made no Preparation beforehand and never committed any minutes of mine to writing.

Before the final Question was put, the new Delegates from New Jersey came in, and Mr. Stockton, one of them Dr. Witherspoon and Mr. Hopkinson, a very respectable Characters, expressed a great desire to hear the Arguments. All was Silence: No one would speak: all Eyes were turned upon me. Mr. Edward Rutledge came to me and said laughing, Nobody will speak but you, upon this Subject. You have all the Topicks so ready, that you must satisfy the Gentlemen from New Jersey. I answered him laughing, that it had so much the Air of exhibiting like an Actor or Gladiator for the Entertainment of the Audience, that I was ashamed to repeat what I had said twenty times before, and I thought nothing new could be advanced by me. The New Jersey Gentlemen however still insisting on hearing at least a Recapitulation of the Arguments and no other Gentleman being willing to speak, I summed up the Reasons, Objections and Answers, in as concise a manner as I could, till at length the Jersey Gentlemen said they were fully satisfied and ready for the Question, which was then put and determined in the Affirmative.” [viii]

JOURNALS OF CONGRESS. CONTAINING THE PROCEEDINGS FROM JANUARY 1, 1776, TO JANUARY 1, 1777, York-town, Pa.: Printed by John Dunlap, 1778, 520, xxvii pp, - This volume of the Journals of Congress, opened to the July 2nd, 1776 proceedings, is one of the rarest of the series issued from 1774 to 1788, and has a peculiar and romantic publication history. Textually the Journals cover all the 1776 events, culminating with the Declaration of Independence on July 4th, an early printing of which appears in the Journals with the names of the signers, as well as the Resolution for Independency and all of the other actions of Congress for the year.

From 1774 to 1777 the printer of the Journals of Congress was Robert Aitken of Philadelphia. In 1777 he published the first issue of the Journals for 1776, under his own imprint. This was completed in the spring or summer. In the fall of 1777 the British campaign under Howe forced the Congress to evacuate Philadelphia, moving first to Lancaster and then to York, Pennsylvania. The fleeing Congress took with it what it could, but, not surprisingly, was unable to remove many copies of its printed Journals, which would have been bulky and difficult to transport. Presumably, any left behind in Philadelphia were destroyed by the British, accounting for the particular scarcity of those volumes today.

Among the material evacuated from Philadelphia were Aiken's printed sheets of pages 1-424 of the 1776 Journals. Having lost many complete copies in Philadelphia, and not having the terminal sheets to make up more copies, Congress resolved to reprint the remainder of the volume. John Dunlap the printer of the July 4th Declaration of Independence Broadside, unlike Aiken, had evacuated his equipment. Consequently, the Continental Congress appointed Dunlap their new printer on May 2, 1778. Dunlap then reprinted the rest of the 1776 volume (coming out to a slightly different pagination from Aitken's version). Dunlap added, under his imprint at York, a new title page along with a notice on the verso of his appointment as printer to Congress. This presumably came out between his appointment on May 2 and the return of Congress to Philadelphia in July 1778.

John Adams wrote Abigail Adams on July 3, 1776:

Consequently, it was the date of July 2, 1776 that John Adams thought would be celebrated by future generations of Americans writing to his wife Abigail Adams a second letter on July 3, 1776:

Broadside Produced during the night of July 4, 1776,

The other printings of the Dunlap Broadside known to exist are dispersed among private owners, American and British institutions. The following are the current know locations of the Dunlap Broadsides.

After the Continental Congress learned N.Y. agreed to the declaration they ordered, on July 19, 1776, that the Declaration be

As the New York delegates had no authority to vote on the question of independence on the 4th of July, they were not authorized to sign the Declaration on that day. On the 15th, however, when the new instructions were received, they had full authority to do so ; and on the 2nd of August such of the delegation as were in the Congress subscribed their names, to wit, William Floyd, Francis Lewis, and Philip Livingston, the latter of whom took his seat in the Congress on the 5th or 6th of July; having, on his representing to the Provincial Congress, on the 26th of June, that his attendance at the Continental Congress was necessary, received permission to leave the Convention after the 29th.

Lewis Morris probably signed in September of 1776. On the 26th of August and on the 3rd of December he was in his seat in the New York Convention. In September and October he was in the Continental Congress.

Of those who were present on the 4th of July, and who did not sign the Declaration, it is sufficient to say, that when the New York delegates received authority to sign it, George Clinton, like John Dickinson, had joined the army, and was in command of the New Jersey Highlands as a Brigadier General. Henry Wisner and Robert B. Livingston also did not return to Philadelphia remaining in their seats at the New York Convention and thus were unable to sign. John Alsop, as already stated, had resigned his seat and opposed independence.

Neither Samuel Chase or Charles Carroll were in Congress on the 4th of July because they were present on that day in the Maryland Convention, then in session at Annapolis. They joined Continental Congress sometime in the middle of July, and signed with the other members on the 2nd of August, as directed by the July 19th resolution, which they voted to enact.

As for the remaining late signers, it is believed that Mathew Thornton subscribed his name as late as November. The signing any additional member was discontinued at the close of the year 1776 except for Thomas McKean who was present on July 4th and signed the Declaration in a subsequent year.

The Engrossed Declaration of Independence was safeguarded all throughout the revolutionary war traveling with the Continental Congress to maintain its safety. The National Archives lists the following locations of the Traveling Declaration since 1776:

Yesterday the greatest Question was decided, which ever was debated in America, and a greater perhaps, never was or will be decided among Men. A Resolution was passed without one dissenting Colony "that these united Colonies, are, and of right ought to be free and independent States, and as such, they have, and of Right ought to have full Power to make War, conclude Peace, establish Commerce, and to do all the other Acts and Things, which other States may rightfully do."You will see in a few days a Declaration setting forth the Causes, which have impell'd Us to this mighty Revolution, and the Reasons which will justify it, in the Sight of God and Man. A Plan of Confederation will be taken up in a few days. On July 2, 1776 the Association known as United Colonies of America officially became the United States of America .[ix]

Was Delaware, Virginia, or New Hampshire the first US State?

But the Day is past. The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America.

I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.

You will think me transported with Enthusiasm but I am not. -- I am well aware of the Toil and Blood and Treasure, that it will cost Us to maintain this Declaration, and support and defend these States. -- Yet through all the Gloom I can see the Rays of ravishing Light and Glory. I can see that the End is more than worth all the Means. And that Posterity will tryumph in that Days Transaction, even altho We should rue it, which I trust in God We shall not. [x]

American Archives compiler Peter Force wrote in his book, The Declaration of Independence, or, Notes on Lord Mahon's history of the American independence that:

The adoption of this resolution on the 2nd of July, 1776, was the termination of all lawful authority of the King over the thirteen United Colonies — made by this act of the Congress thirteen United States of America. The Americans now owed no more allegiance to England than they owed to Germany, or France, or Spain ; they were no longer rebels or insurgents ; they claimed their recognition as one among the family of nations of the earth, and they maintained and sustained the claim. It was in the end acknowledged by the King of England himself. After the 2nd of July, 1776, the English armies, with their Hessian allies, were the invaders of America, sent to reduce the independent States to unconditional submission to the Crown of England. And yet this day has no place in Lord Mahon's "history," the day on which was consummated the most important measure that had ever been debated in America.

Amazingly, in 21st Century, this very day still remains a mere footnote in United States history.

After the July 2nd, 1776, Resolution for Independency was passed, the Second Continental Congress turned to the debate over the language in the Committee of Five's formal Declaration of Independence. Time was short and Congress adjourned until Wednesday the 3rd. The debates of July 3rd and 4th altered the manuscript and with these changes the Declaration of Independence was considered by the committee of the whole. Thomas Jefferson was disappointed by the "depredations" made by Congress writing:

After the July 2nd, 1776, Resolution for Independency was passed, the Second Continental Congress turned to the debate over the language in the Committee of Five's formal Declaration of Independence. Time was short and Congress adjourned until Wednesday the 3rd. The debates of July 3rd and 4th altered the manuscript and with these changes the Declaration of Independence was considered by the committee of the whole. Thomas Jefferson was disappointed by the "depredations" made by Congress writing:

The pusillanimous idea that we had friends in England worth keeping terms with, still haunted the minds of many. For this reason those passages which conveyed censure on the people of England were struck out, lest they should give them offense. The clause too, reprobating the enslaving the inhabitants of Africa, was struck out in compliance to South Carolina and Georgia, who had never attempted to restrain the importation of slaves, and who on the contrary still wished to continue it. Our Northern brethren also I believe felt a little tender under these censures; for tho' their people have very few slaves themselves yet they had been pretty considerable carriers of them to others. [xi]

Despite these July 4th changes and previous committee edits Jefferson is rightfully considered the main author of the Declaration of Independence. John Adams in his autobiography recalls this of Jefferson’s pen:

The Committee had several meetings, in which were proposed the Articles of which the Declaration was to consist, and minutes made of them. The Committee then appointed Mr. Jefferson and me, to draw them up in form, and cloath them in a proper Dress. The Sub Committee met, and considered the Minutes, making such Observations on them as then occurred: when Mr. Jefferson desired me to take them to my Lodgings and make the Draught. This I declined and gave several reasons for declining. 1. That he was a Virginian and I a Massachusettensian. 2. that he was a southern Man and I a northern one. 3. That I had been so obnoxious for my early and constant Zeal in promoting the Measure, that any draught of mine, would undergo a more severe Scrutiny and Criticism in Congress, than one of his composition. 4thly and lastly and that would be reason enough if there were no other, I had a great Opinion of the Elegance of his pen and none at all of my own. I therefore insisted that no hesitation should be made on his part. He accordingly took the Minutes and in a day or two produced to me his Draught. [xii]

Late in the afternoon on July 4th, 1776 twelve of the thirteen colonies an reached agreement to formally proclaim themselves as free and independent nations. Only New York was the lone holdout and it was due to the fact the Delegates were not granted the authority to vote yea or nay on Independence.

This was a Proclamation that was long overdue as the fighting between the American colonists and the British forces had been going on for over a year. The Declaration, on July 4th, 1776, firstly memorialized what history has judged to be a just, moral and most persuasive treatise on why the colonies had the right to declare their independence from Great Britain. The July 2nd vote put the world on notice of the Colonies’ independence. It was, however, the Declaration’s proclamations that were designed to win the hearts and minds of the American Colonists who would be asked to continue a seemingly insuperable war against King and country. Therefore, it was essential that the Delegates not rely on the newspapers to disseminate its message to the people as most colonists could not afford the cost of purchasing a paper. Consequently, in the evening of July 4, 1776 John Hancock's Congress ordered:

This was a Proclamation that was long overdue as the fighting between the American colonists and the British forces had been going on for over a year. The Declaration, on July 4th, 1776, firstly memorialized what history has judged to be a just, moral and most persuasive treatise on why the colonies had the right to declare their independence from Great Britain. The July 2nd vote put the world on notice of the Colonies’ independence. It was, however, the Declaration’s proclamations that were designed to win the hearts and minds of the American Colonists who would be asked to continue a seemingly insuperable war against King and country. Therefore, it was essential that the Delegates not rely on the newspapers to disseminate its message to the people as most colonists could not afford the cost of purchasing a paper. Consequently, in the evening of July 4, 1776 John Hancock's Congress ordered:

That the declaration be authenticated and printed That the committee appointed to prepare the declaration superintend and correct the press. That the copies of the declaration be sent to the several assemblies, conventions and committees, or councils of safety, and to the several commanding officers of the Continental troops, and that it be proclaimed in each of the United States, and at the head of the army. [xiii]

In accordance with the above order Philadelphia printer John Dunlap was given the task to print broadside copies of the agreed-upon declaration to be signed in type only by Continental Congress President John Hancock and Secretary Charles Thomson. Since New York had not approved the Declaration of Independence the word Unanimous does not appear on the July 4, 1776 Broadside.

Broadside Produced during the night of July 4, 1776,

by printer John Dunlap - Courtesy of the National Archives

Authenticate your Declaration of Independence Click Here

John Dunlap is thought to have printed 200 Broadsides that July 4th evening which were distributed to the members of Congress on July 5th. It is a known fact that John Hancock sent a copy on July 5th, 1776 to the Committee of Safety of Pennsylvania, a copy to the Convention of New Jersey, and a copy to Colonel Haslet with instructions to have it read at the head of his battalion. In addition John Adams sent one copy, and Elbridge Gerry two copies, to friends.

All this was done. It was also printed and circulated among the people, in all the cities, towns, and villages, wherever a printing press was found. It was read everywhere — in churches, in the courts, at all gatherings of the people, and in every private company and family circle. It was this universal diffusion of the Declaration that made the 4th of July the great festival day of the nation, instead of the 2nd day of July, the real birthday of American freedom.

The Declaration, as affirmatively voted on July 4th, was not signed on that day by the attending delegates. It also should be remembered that on the 4th of July it was "a Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled," as it is found on the journal at this day. It had not then the sanction of New York, whose delegates were without authority to vote on the question, and it could not then be called a unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States. When it received the sanction of New York, and not till then, it was " the unanimous Declaration." This was well understood in the Congress, and is mentioned in a letter from Mr. Gerry to General Warren, dated Philadelphia, July 5, 1776, in which he says:

New York will, most probably, on Monday next, when its Convention meets for forming a Constitution, join in the measure, and then it will be entitled " the unanimous Declaration of the thirteen United States of America.

The New York Delegates were required by their legislature to abstain from voting or signing any instrument of independence. John Hancock in an attempt to quickly gain the unanimous consent from all thirteen colonies sent a Dunlap broadside off to the NY Provincial Congress on Saturday July 6th.

The Declaration of Independence arrived, along with the NY Continental Congress Delegates' July 2nd letter at the Provincial NY Congress new meeting site at White Plains on July 9th. The members, at once, referred the letter and a a copy of the Declaration of Independence to a committee from headed by John Jay who had been an absent member from the Continental Congress due to his duties in the New York Provincial Congress. John Jay, as chairman, reported a resolution of his own drafting, which was unanimously adopted independence: "That the reasons assigned by the Continental Congress for declaring the United Colonies free and independent States are cogent and conclusive; and that while we lament the cruel necessity which has rendered that measure unavoidable, we approve the same, and will, at the risk of our lives and fortunes, join with the other colonies in supporting it." [xiv] NY also adopted Jay's resolution that "five hundred copies of the Declaration of Independence be ... published in handbills and sent to all the County committees in this State." The next day the style of the New York House was changed to the "Convention of the Representatives of the State of New York."

The New York Resolution was laid before the Continental Congress on July 15th so then and not before was it proper to entitle the document "The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen States of America." Among the resolutions passed by the Continental Congress on July, 4th 1776 was one that called for the President John Hancock to send to several commanding officers of the Continental army Dunlap printings of the Declaration of Independence, Hancock sent a copy of the resolutions together with the "Dunlap Broadside" of the Declaration to General George Washington on July 6, 1776. Washington had the Declaration read to his assembled troops in New York on July 9th. Later that night, the Americans destroyed a bronze and lead statue of King George III, which stood at the foot of Broadway on the Bowling Green in celebration of the Nation’s Independence. Washington's personal copy of the Dunlap printing of the Declaration of Independence remains in the Manuscript Division's George Washington Papers .[xxviii]

Declaration of Independence broadsides were also sent to US Ministers Benjamin Franklin and Silas Deane in France, who were to disseminate copies to the Royal Houses in Europe. We know, by evidence of Silas Deane's December 1, 1776 letter to the French Court that these broadsides were intercepted at sea:

Declaration of Independence broadsides were also sent to US Ministers Benjamin Franklin and Silas Deane in France, who were to disseminate copies to the Royal Houses in Europe. We know, by evidence of Silas Deane's December 1, 1776 letter to the French Court that these broadsides were intercepted at sea:

Dated Paris, December 1, 1776May it please your Excellency.In obedience to the Orders of the honourable Congress of the United States of North America I have the honor of presenting to your Excellency the inclosed Declaration of their independence.This Declaration was dispatched to Me immediately after its being resolv’d on, but by accidents of War was intercepted, or it would have been much earlier presented. . . . during this accidental delay the United States have had a striking instance of the generous, tho just, & impartial principles by which his most Catholic Majesty is actuated, in the Treatment which their Gospels have met with in his Ports. This merits the most sincere and grateful acknowledgments of the United States, and as their agent I humbly wish the same may be express’d in the warmest Terms to his most Catholic Majesty and that he may be assured the United States will ever retain the most lively sense, of his impartial justice. I must excuse myself for addressing Your Excellency in English on Acct of my imperfect knowledge of other European Languages, and to assure you that I am with the most profound respect.Your Excellency’s most Obed’t & very humble servtSILAS DEANEAgent for the United States in North America.

Two days earlier a letter, which included a Declaration of Independence Broadside that was signed and attested by Benjamin Franklin and Silas Deane as the Commissioners Plenipotentiary, was sent to Frederick The Great through the Prussian Minister, Baron De Scolenberg.

November 28, 1776

May it please Your ExcellencyWe have the honor of enclosing the DECLARATION of the INDEPENDENCE of the UNITED STATES of NORTH AMERICA, with the ARTICLES of CONFEDERATION; which we desire you to take the earliest Opportunity, of laying before his Majesty, The King of Prussia; at the same time we wish he may be assured, of the earnest desire, of the United States, to obtain his Friendship; & by a free Commerce, to establish an intercourse between their distant Countries, which they are confident must be mutually beneficial. The state of the Commerce of the United States, and the advantages which must result to both Countries, from the Establishment of a Commercial intercourse; we shall if agreeable to his Majesty, lay before him. Meantime we take the Liberty of assuring your Excellency that the Reports of the advantages gained by his Britannic Majesty’s Troops, over those of the United States are greatly exaggerated, and many of them without Foundation, especially those which assert that an accommodation is about to take place, there being no probability of such an Event, by the latest intelligence, we have received from America.We have the honor to be with the most profound respectYours Excellency’s Most Obedient & Very Humble ServtsB. FRANKLINS. DEANECommissioners Plenipotentiary For The United States Of North AmericaMinister Baron Von Scolenderg

Today less than thirty of these Dunlap broadsides are known to exist. The original working copy(ies) of the Declaration of Independence that were authenticated by President Hancock and Secretary Thomson on July 4, 1776 is/are lost. All we have left from the actual July 4th event are the drafts and printings of John Dunlap. One of these unsigned "Dunlap Broadsides", as it reported to have sold for $8.14 million in an August 2000 New York City Auction. [xv] This copy was discovered in 1989 by a man browsing in a flea market who purchased a painting for four dollars because he was interested in the frame. Concealed in the backing of the frame was an original Dunlap Broadside of the Declaration of Independence. This Dunlap Broadside has since been sold privately for nearly three times that August 2000 auction price.

Harvard University, Houghton Library - Massachusetts Historical Society - Yale University, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library - New York Historical Society - New York Public Library - American Philosophical Society - Historical Society of Pennsylvania - Independence National Historical Park - Maryland Historical Society - Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division - Library of Congress, Manuscript Division - National Archives and Records Service -Indiana University, Lilly Library -University of Virginia, Alderman Library - Public Record Office, London, England (Admiralty Records) - Public Record Office, London, England (Colonial Office 5) - Chicago Historical Society - Maine Historical Society - William H. Scheide, Scheide Library, Princeton, New Jersey - Ira G. Corn, Jr., and Joseph P. Driscoll, Dallas, Texas - Anonymous, New York, New York - Chew Family, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania - John Gilliam Wood, Edenton, North Carolina - Anonymous, purchased at Sotheby's, December 1990 - Visual Equities, Inc., Atlanta, Georgia [xvi]

In 1776 as the Delegates returned home with their personal copies of the Dunlap Broadside each State decided on how to disseminate the Declaration of Independence to its citizens. Some states, like Virginia, chose newspapers while others, like New York, ordered official State Broadsides to be printed from the Dunlap Declaration of Independence. The official printing, for instance, ordered by Massachusetts was to be distributed to ministers of all denominations, to be read to their congregations. News of the declaration was proclaimed in every parish of Massachusetts via this state printed broadside. In the absence of other media, broadsides were subsequently distributed out among the colonies and tacked to the walls of churches and other meeting places to spread news of America's independence. These state broadsides all had the July 4th date but many adding the corrected language "Unanimous Declaration" to their headings with NY's ascension on July 9th.

Declaration of Independence Massachusetts Broadside

Image Courtesy of Stanley L. Klos

DOI was replevined in 2001 by the State of Maine

Authenticate your Declaration of Independence Click Here

Another Philadelphia Printer, Henrich Millers, produced a German Newspaper in 1776 called the Pennsylvanisher Staatsbote. On July 9, 1776 the newspaper printed a full German translation of the American Declaration of Independence and reported:

Yesterday at noon, the Declaration of Independence, which is published on this news paper's front page, was publicly proclaimed in English from an elevated platform in t he courtyard of the State House. Thereby the United Colonies of North America were absolved from all previously pledged allegiance to the king of Great Britain, they are and henceforth will be totally free and independent. The proclamation was read by Colonel Nixon, sheriff Dewees stood by his side and many members of the Congress, of the [Pennsylvania] Assembly, generals and other high army officers were also present. Several thousand people were in the courtyard to witness the solemn occasion. After the reading of the Declaration there were three cheers and the cry: God bless the free states of North America! To this every true friend of these colonies can only say, Amen. [xvii]

Miller did prepare a full printing of the Declaration of Independence in a German-language broadside on July 9th but historian Karl J.R. Arndt of Clark University claims Miller was trumped by German printers Cist and Steiner. According to Clark, Cist and Steiner produced an ordinary laid paper German Declaration of Independence broadside, without a watermark, measuring 16 inches by 12 3/4 inches as early as July 6th, the day after Dunlap's printing .The author had the privilege to inspect and hold this historic broadside that is now in the archives of Gettysburg College. At the bottom center of the Declaration there is an imprint appears as "Philadelphia: Gedruckt bey Steiner und Cist, in der Zweyten-strasse."

|

| Am Dienstag, den 9. Juli 1776, erschien in Henrich Millers Pennsylvanischer Staatsbote die deutsche Übersetzung der amerikanischen Unabhängigkeitserklärung. On Tuesday, 9th of July 1776, the German translation of the American Declaration of Independence appeared in Henrich Miller's "Pennsylvanischer Staatsbote". Photo: Göttingen, Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek |

Contrary to popular belief, two original July 5th, 1776 Dunlap printed broadsides with only Hancock and Thomson's names were the actual documents delivered to King George III notifying him of the resolution to absolve all ties with Great Britain. King George III never received a signed copy with a John Hancock’s signature large enough for him to read without his spectacles. Aside from the Dunlap and Massachusetts broadsides there are 12 other known contemporary broadside editions of the Declaration of Independence. Nine have imprints identifying their printers and place of publication, while five carry no imprint. The low survival rate of all of the contemporary regional printings of the Declaration-which were both utilitarian and intrinsically ephemeral-makes identification of their printers particularly difficult. None of these have the names of the other signers aside from John Hancock and Charles Thomson. The other names of the signers were not made public until 1777.

The Engrossed Declaration of Independence

fairly engrossed on parchment, with the title and stile [sic] of 'The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America,' and that the same, when engrossed, be signed by every member of Congress. [xx]

This was the first order for signing the Declaration of Independence. The order on July 4th had called for no delegate signatures except that it be only authenticated by the President and Secretary of the Continental Congress and printed. This new July 19th, 1776 order was not that the Declaration of Independence be signed by the members present on the 4th of July or on any other day. The order required that the Declaration of Independence was to be "signed" by every member of the Congress.

Timothy Matlack, a Pennsylvanian who had assisted the Secretary of the Congress, Charles Thomson is believed to have prepared the official document, according to the July 19th order, in his large and clear hand. Matlack was also the "scribe" who wrote out George Washington's commission as commanding general of the Continental Army which was also signed by President John Hancock. Finally on August 2, 1776 the journal of the Continental Congress record reports: "The declaration of independence being engrossed and compared at the table was signed," which contradicts the popular belief that the Declaration was executed by all the delegates in attendance on July 4, 1776.

Notes on the signers:

The August 2nd, 1776 signing explains why Delegate John Dickinson's name, along with others, are not found among the signers of the Declaration of independence. Dickinson was not in Congress on the 2nd of August, 1776, when it received its first signatures, nor afterwards in that year. It is necessary to understand that because his name is not there, it is by no means to be inferred that he was in the slightest degree disaffected to the cause.

John Dickinson, like Robert Morris, was opposed to independence on the grounds that the measure was premature. Morris and Dickinson opposed the resolution in debate, and voted against it when the question was taken on the 1st of July; but both, when the decision was made, acquiesced in the measure, and gave it their earnest, firm, and cordial support. In early July, Mr. Dickinson marched with the regiment he commanded to Elizabethtown, New Jersey. Dickinson remained at his post until the regiment was discharged in the following September. In the meantime a new Pennsylvania delegation was chosen by a state convention. Robert Morris was retained, but Mr. Dickinson was not reelected. On the 2nd of August, therefore, Robert Morris was in the Congress, and signed the Declaration while John Dickinson, who was no longer a member was not authorized to sign it.

Mr. John Alsop, of New York was another member of the July 4th Continental Congress who opposed independence. Unlike John Dickinson, Alsop appears actually opposed to independence on July 4th and beyond. On the 15th of July, when the resolutions of the New York Convention of the 9th, approving the Declaration, were read in Congress, Mr. Alsop remained vehemently opposed. The next day he addressed a letter to the Convention, expressing his dissatisfaction at the course which had been pursued. Alsop writes:

I am compelled, therefore, to declare that it is against my judgment and inclination. As long as a door was left open for a reconciliation with Great Britain upon honourable and just terms, I was willing and ready to render my country all the service in my power, and for which purpose I was appointed and sent to this Congress ; but as you have, I presume, by that Declaration closed the door of reconciliation, I must beg leave to resign my seat as a delegate from New York, and that I may be favoured with an answer and my dismission.

On the 22nd of July the Convention resolved unanimously, "That the Convention do cheerfully accept of Mr. Alsop's resignation of his seat in the Continental Congress, and that Mr. Alsop be furnished with a copy of this resolution." Consequently, Delegate Alsop, despite being one of the members present on the 4th of July did not sign the Declaration.

Thomas McKean, of Delaware, was present in the Congress of the 2nd of July, and voted for the Resolution of Independence, yet his name was not subscribed to the Declaration in 1776. Like John Dickinson, he commanded a regiment, and early in July marched to the Jerseys. When discharged from his military duties he attended the Convention of Delaware, which met on the 27th of August to form a State Constitution, and was dissolved on the 21st of September, 1776, after which he resumed his seat in Congress.

On the 8th of November, when the Delegates to Congress from Delaware were chosen by the Assembly of that State, Mr. McKean was not re-elected; nor was he again appointed a Delegate until the 17th of December, 1777. Additionally, McKean's name does not appear on the Declaration of Independence as signer in the 1777 printing of the 1776 Journals of Congress by either Robert Aiken or even in John Dunlap's 1778 reprint of the 1776 Journals. His name, however, appears on the engrossed copy, which indicates a signing in 1778 or as late as 1781 when he was President of the United States in Congress Assembled.

On the 2nd of July five delegates from New York were present in Congress, namely, George Clinton, Henry Wisner, William Floyd, Francis Lewis, and John Alsop, as appears by a letter of that date to the Provincial Congress, asking for instructions on the question of independence. Neither Philip Livingston nor Lewis Morris were present on that day. Yet their names are found on the Declaration of the 4th, while those of Clinton and Wisner and Alsop are not found there.

On the 2nd of July five delegates from New York were present in Congress, namely, George Clinton, Henry Wisner, William Floyd, Francis Lewis, and John Alsop, as appears by a letter of that date to the Provincial Congress, asking for instructions on the question of independence. Neither Philip Livingston nor Lewis Morris were present on that day. Yet their names are found on the Declaration of the 4th, while those of Clinton and Wisner and Alsop are not found there.

As the New York delegates had no authority to vote on the question of independence on the 4th of July, they were not authorized to sign the Declaration on that day. On the 15th, however, when the new instructions were received, they had full authority to do so ; and on the 2nd of August such of the delegation as were in the Congress subscribed their names, to wit, William Floyd, Francis Lewis, and Philip Livingston, the latter of whom took his seat in the Congress on the 5th or 6th of July; having, on his representing to the Provincial Congress, on the 26th of June, that his attendance at the Continental Congress was necessary, received permission to leave the Convention after the 29th.

Lewis Morris probably signed in September of 1776. On the 26th of August and on the 3rd of December he was in his seat in the New York Convention. In September and October he was in the Continental Congress.

Of those who were present on the 4th of July, and who did not sign the Declaration, it is sufficient to say, that when the New York delegates received authority to sign it, George Clinton, like John Dickinson, had joined the army, and was in command of the New Jersey Highlands as a Brigadier General. Henry Wisner and Robert B. Livingston also did not return to Philadelphia remaining in their seats at the New York Convention and thus were unable to sign. John Alsop, as already stated, had resigned his seat and opposed independence.

Neither Samuel Chase or Charles Carroll were in Congress on the 4th of July because they were present on that day in the Maryland Convention, then in session at Annapolis. They joined Continental Congress sometime in the middle of July, and signed with the other members on the 2nd of August, as directed by the July 19th resolution, which they voted to enact.

As for the remaining late signers, it is believed that Mathew Thornton subscribed his name as late as November. The signing any additional member was discontinued at the close of the year 1776 except for Thomas McKean who was present on July 4th and signed the Declaration in a subsequent year.

John Hancock, the President of the Congress, was the first to sign the sheet of parchment measuring 24¼ by 29¾ inches. He used a bold signature centered below the text. In accordance with prevailing custom, the other delegates began to sign at the right below the text, their signatures arranged according to the geographic location of the states they represented. New Hampshire, the northernmost state, began the list, and Georgia, the southernmost, ended it. Eventually 56 delegates signed, although all were not present on August 2. Among the later signers were Elbridge Gerry, Oliver Wolcott, Lewis Morris, Thomas McKean, and Matthew Thornton, who found that he had no room to sign with the other New Hampshire delegates. A few delegates who voted for adoption of the Declaration on July 4 were never to sign in spite of the July 19 order of Congress that the engrossed document "be signed by every member of Congress.

Non-signers included John Dickinson, who clung to the idea of reconciliation with Britain, and Robert R. Livingston, one of the Committee of Five, who thought the Declaration, was premature." [xxi]

Click Here to View the ink stand used to sign the Declaration of Independence

Thank you Ranger Stewart A. W. Low

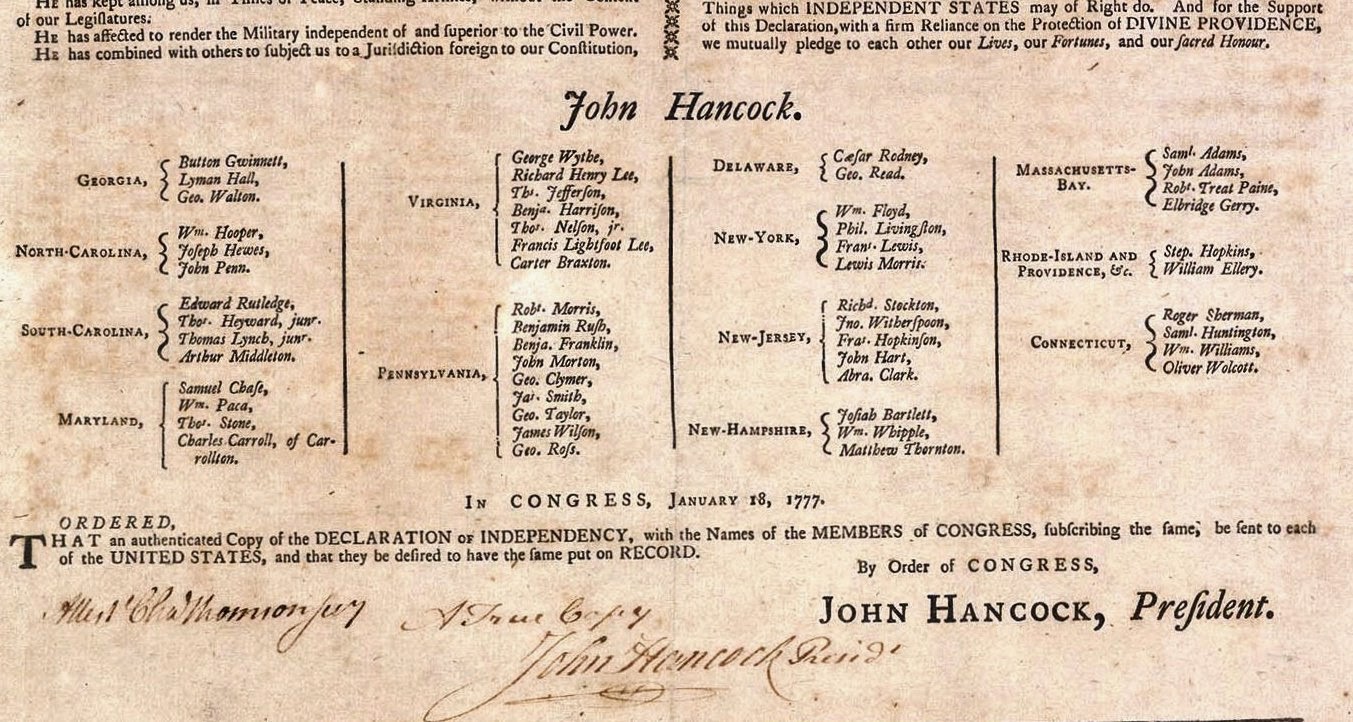

In late 1776, the Continental Congress fled to Baltimore, Maryland due to mounting British victories and their advancement towards Philadelphia. Congress re-convened on December 20th, 1776 and stayed in session until March 4th, 1777. On January 18th, 1777, after victories at Trenton and Princeton, John Hancock's Continental Congress ordered that a true copy of the Unanimous Declaration of The Thirteen United States of America be printed complete with the names of all the signers.

Mary Katherine Goddard, a Baltimore Postmaster, printer and publisher, was given the original engrossed copy of the Declaration to set the type in her shop. A copy of the 1777 Goddard printing was ordered to be sent to each state so the people would know the names of the signers:

Mary Katherine Goddard, a Baltimore Postmaster, printer and publisher, was given the original engrossed copy of the Declaration to set the type in her shop. A copy of the 1777 Goddard printing was ordered to be sent to each state so the people would know the names of the signers:

Ordered, That an authenticated copy of the Declaration of Independency, with the names of the members of Congress subscribing the same, be sent to each of the United States, and that they be desired to have the same put upon record. [xviii]

Authenticate your Declaration of Independence Click Here

Today, there are nine known Goddard broadsides that can be found.Library of Congress, Connecticut State Library of the late John W. Garrett, Maryland Hall of Records, Maryland Historical Society, Massachusetts Archives, New York Public Library, Library Company of Philadelphia, Rhode Island State Archives. [xix]

|

| 1777 Declaration of Independence Goddard Broadside Signatures |

The Goddard printing remains the only Declaration of Independence Broadside, ordered by the Continental Congress, with the 55 signers names included in the document. Only Delegate Thomas McKean, whose signature appears on the engrossed Declaration of Independence, is absent from this 1777 Broadside.

|

| Mary Katherine Goddard was a 18th Century Baltimore Postmaster, printer and publisher |

The Engrossed Declaration of Independence was safeguarded all throughout the revolutionary war traveling with the Continental Congress to maintain its safety. The National Archives lists the following locations of the Traveling Declaration since 1776:

Philadelphia: August-December 1776 Baltimore: December 1776-March 1777 Philadelphia: March-September 1777 Lancaster, PA: September 27, 1777 York, PA: September 30, 1777- June 1778 Philadelphia: July 1778-June 1783 Princeton, NJ: June-November 1783 Annapolis, MD: November 1783-October 1784 Trenton, NJ: November-December 1784 New York: 1785-1790 Philadelphia: 1790-1800 Washington, DC (three locations): 1800-1814 Leesburg, VA: August-September 1814 Washington, DC (three locations): 1814-1841 Washington, DC (Patent Office Building): 1841-1876 Philadelphia: May-November 1876 Washington, DC (State, War, and Navy Building): 1877-1921 Washington, DC (Library of Congress): 1921-1941 Fort Knox*: 1941-1944 Washington, DC (Library of Congress): 1944-1952 Washington, DC (National Archives): 1952-present *Except that the document was displayed on April 13, 1943, at the dedication of the Thomas Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D. C. [xxii]

The original Declaration, now exhibited in the Rotunda of the National Archives Building in Washington, DC, has faded badly -- largely because of poor preservation techniques during the 19th century and the wet ink transfer process of 1820 utilized to make vellum copies.

It is important we digress here to explain the history and process that virtually eradicated most of the ink on the othe engrossed signed Declaration of Independence that has become our national icon.

By 1820 the condition of the only signed Declaration of Independence was rapidly deteriorating. In that year John Quincy Adams, then Secretary of State, commissioned William J. Stone of Washington to create exact copies of the Declaration using a "new" Wet-Ink Transfer process. Unfortunately this Wet-Ink Transfer greatly contributed to the degradation of the only engrossed and signed Declaration of Independence ever produced.

On April 24, 1903 the National Academy of Sciences reported its findings, summarizing the physical history of the Declaration:

It is important we digress here to explain the history and process that virtually eradicated most of the ink on the othe engrossed signed Declaration of Independence that has become our national icon.

By 1820 the condition of the only signed Declaration of Independence was rapidly deteriorating. In that year John Quincy Adams, then Secretary of State, commissioned William J. Stone of Washington to create exact copies of the Declaration using a "new" Wet-Ink Transfer process. Unfortunately this Wet-Ink Transfer greatly contributed to the degradation of the only engrossed and signed Declaration of Independence ever produced.

On April 24, 1903 the National Academy of Sciences reported its findings, summarizing the physical history of the Declaration:

The instrument has suffered very seriously from the very harsh treatment to which it was exposed in the early years of the Republic. Folding and rolling have creased the parchment. The wet press-copying operation to which it was exposed about 1820, for the purpose of producing a facsimile copy, removed a large portion of the ink. Subsequent exposure to the action of light for more than thirty years, while the instrument was placed on exhibition, has resulted in the fading of the ink, particularly in the signatures. The present method of caring for the instrument seems to be the best that can be suggested.

The committee does not consider it wise to apply any chemicals with a view to restoring the original color of the ink, because such application could be but partially successful, as a considerable percentage of the original ink was removed in making the copy about 1820, and also because such application might result in serious discoloration of the parchment; nor does the committee consider it necessary or advisable to apply any solution, such as collodion, paraffin, etc., with a view to strengthening the parchment or making it moisture proof.

The committee is of the opinion that the present method of protecting the instrument should be continued; that it should be kept in the dark, and as dry as possible, and never placed on exhibition." [xxiii]

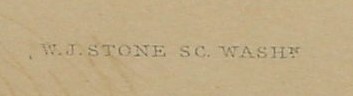

The Wet-Ink Transfer Process called for the surface of the Declaration to be moistened transferring some of the original ink to the surface of a clean copper plate. Three and one-half years later under the date of June 4, 1823, the National Intelligencer reported that:

the City Gazette informs us that Mr. Wm. J. Stone, a respectable and enterprising (sic) engraver of this City has, after a labor of three years, completed a facsimile of the Original of the Declaration of Independence, now in the archives of the government, that it is executed with the greatest exactness and fidelity; and that the Department of State has become the purchaser of the plate. The facility of multiplying copies of it, now possessed by the Department of State will render furthur (sic) exposure of the original unnecessary."[xxiv]

|

Wet Ink Transfer Engraved Declaration of Independence

printing Circa 1823 -- Stanley Yavneh Klos Collection

|

Vellum Declaration Of Independence Engraver Mark left side: "Engraved by W. J. Stone, for Dept of State, by order of " - image courtesy of Historic.us |

|

Vellum Declaration Of Independence W. J. Stone Engraver Mark Right Side: "J Q Adams Sect of State, July 4th, 1823" - image courtesy of Historic.us |

That two hundred copies of the Declaration, now in the Department of State, be distributed in the manner following: two copies to each of the surviving Signers of the Declaration of Independence (John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Charles Carroll of Carrollton); two copies to the President of the United States (Monroe); two copies to the Vice-President of the United States (Tompkins); two copies to the late President, Mr. Madison; two copies to the Marquis de Lafayette, twenty copies for the two houses of Congress; twelve copies for the different departments of the Government (State, Treasury, Justice, Navy, War and Postmaster); two copies for the President's House; two copies for the Supreme Court room, one copy to each of the Governors of the States; and one to each of the Governors of the Territories of the United States; and one copy to the Council of each Territory; and the remaining copies to the different Universities and Colleges of the United States, as the President of the United States may direct. [xxv]

The 201 official parchment copies struck from the Stone plate carry the identification "Engraved by W. J. Stone for the Department of State, by order" in the upper left corner followed by "of J. Q. Adams, Sec. of State July 4th 1824." in the upper right corner. "Unofficial" copies that were struck later do not have the identification at the top of the document or are the printed on vellum. Instead the engraver identified his work by engraving "W. J. Stone SC. Washn." near the lower left corner and burnishing out the earlier identification. Today 33 of the 201 Stone facsimiles printed in 1823 are known to exist. [xxvi] Additionally, three 1823 “proof” paper strikes of the Declaration have recently appeared in public auctions in 2005, 2006 and 2007.

American Archives: Fourth & fifth series : containing a documentary history of the United States of America from the Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776 to the definitive treaty of peace with Great Britain, September 3, 1783 by Peter Force and Published by M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, Washington DC, 1848-1853 - image courtesy of Historic.us

|

Peter Force Declaration Of Independence American Archives printing W. J. Stone Mark - image courtesy of Historic.us |

After the 1823 printing, the original plate was altered for Peter Force to include rice paper copies in a series of books titled American Archives: Fourth & fifth series : containing a documentary history of the United States of America from the Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776 to the Definitive Treaty of Peace with Great Britain, September 3, 1783 by Peter Force and Published by M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, Washington DC, 1848-1853. The purpose of this work was to compile the History of the United States 1774 through 1783. American Archives were also to include the reproduction of key founding documents of the United States. For that occasion the "Wet Ink" copper plate was removed from storage and altered to reflect the Rice Paper printing. On July 21, 1833 the original engraver, William Stone, invoiced Peter Force for 4,000 imprints of the Declaration. After mounting expenses and increasing delays in producing American Archives Series IV, by 1843, when Force received Congressional re-authorization, he had scaled back the subscription plan to 500 copies.

William Stone Copper Plate and 1976 Printing Photo

Courtesy of the National Archives

It is not known precisely how many second edition "wet ink transfers" survive but less then six unfolded copies are know by this author. [xxvii]

Chart Comparing Presidential Powers

of America's Four United Republics - Click Here

of America's Four United Republics - Click Here

United Colonies and States First Ladies

1774-1788

United Colonies Continental Congress

|

President

|

18th Century Term

|

Age

|

Elizabeth "Betty" Harrison Randolph (1745-1783)

|

09/05/74 – 10/22/74

|

29

| |

Mary Williams Middleton (1741- 1761) Deceased

|

Henry Middleton

|

10/22–26/74

|

n/a

|

Elizabeth "Betty" Harrison Randolph (1745–1783)

|

05/20/ 75 - 05/24/75

|

30

| |

Dorothy Quincy Hancock Scott (1747-1830)

|

05/25/75 – 07/01/76

|

28

| |

United States Continental Congress

|

President

|

Term

|

Age

|

Dorothy Quincy Hancock Scott (1747-1830)

|

07/02/76 – 10/29/77

|

29

| |

Eleanor Ball Laurens (1731- 1770) Deceased

|

Henry Laurens

|

11/01/77 – 12/09/78

|

n/a

|

Sarah Livingston Jay (1756-1802)

|

12/ 10/78 – 09/28/78

|

21

| |

Martha Huntington (1738/39–1794)

|

09/29/79 – 02/28/81

|

41

| |

United States in Congress Assembled

|

President

|

Term

|

Age

|

Martha Huntington (1738/39–1794)

|

03/01/81 – 07/06/81

|

42

| |

Sarah Armitage McKean (1756-1820)

|

07/10/81 – 11/04/81

|

25

| |

Jane Contee Hanson (1726-1812)

|

11/05/81 - 11/03/82

|

55

| |

Hannah Stockton Boudinot (1736-1808)

|

11/03/82 - 11/02/83

|

46

| |

Sarah Morris Mifflin (1747-1790)

|

11/03/83 - 11/02/84

|

36

| |

Anne Gaskins Pinkard Lee (1738-1796)

|

11/20/84 - 11/19/85

|

46

| |

Dorothy Quincy Hancock Scott (1747-1830)

|

11/23/85 – 06/06/86

|

38

| |

Rebecca Call Gorham (1744-1812)

|

06/06/86 - 02/01/87

|

42

| |

Phoebe Bayard St. Clair (1743-1818)

|

02/02/87 - 01/21/88

|

43

| |

Christina Stuart Griffin (1751-1807)

|

01/22/88 - 01/29/89

|

36

|

Constitution of 1787

First Ladies |

President

|

Term

|

Age

|

April 30, 1789 – March 4, 1797

|

57

| ||

March 4, 1797 – March 4, 1801

|

52

| ||

Martha Wayles Jefferson Deceased

|

September 6, 1782 (Aged 33)

|

n/a

| |

March 4, 1809 – March 4, 1817

|

40

| ||

March 4, 1817 – March 4, 1825

|

48

| ||

March 4, 1825 – March 4, 1829

|

50

| ||

December 22, 1828 (aged 61)

|

n/a

| ||

February 5, 1819 (aged 35)

|

n/a

| ||

March 4, 1841 – April 4, 1841

|

65

| ||

April 4, 1841 – September 10, 1842

|

50

| ||

June 26, 1844 – March 4, 1845

|

23

| ||

March 4, 1845 – March 4, 1849

|

41

| ||

March 4, 1849 – July 9, 1850

|

60

| ||

July 9, 1850 – March 4, 1853

|

52

| ||

March 4, 1853 – March 4, 1857

|

46

| ||

n/a

|

n/a

| ||

March 4, 1861 – April 15, 1865

|

42

| ||

February 22, 1862 – May 10, 1865

| |||

April 15, 1865 – March 4, 1869

|

54

| ||

March 4, 1869 – March 4, 1877

|

43

| ||

March 4, 1877 – March 4, 1881

|

45

| ||

March 4, 1881 – September 19, 1881

|

48

| ||

January 12, 1880 (Aged 43)

|

n/a

| ||

June 2, 1886 – March 4, 1889

|

21

| ||

March 4, 1889 – October 25, 1892

|

56

| ||

June 2, 1886 – March 4, 1889

|

28

| ||

March 4, 1897 – September 14, 1901

|

49

| ||

September 14, 1901 – March 4, 1909

|

40

| ||

March 4, 1909 – March 4, 1913

|

47

| ||

March 4, 1913 – August 6, 1914

|

52

| ||

December 18, 1915 – March 4, 1921

|

43

| ||

March 4, 1921 – August 2, 1923

|

60

| ||

August 2, 1923 – March 4, 1929

|

44

| ||

March 4, 1929 – March 4, 1933

|

54

| ||

March 4, 1933 – April 12, 1945

|

48

| ||

April 12, 1945 – January 20, 1953

|

60

| ||

January 20, 1953 – January 20, 1961

|

56

| ||

January 20, 1961 – November 22, 1963

|

31

| ||

November 22, 1963 – January 20, 1969

|

50

| ||

January 20, 1969 – August 9, 1974

|

56

| ||

August 9, 1974 – January 20, 1977

|

56

| ||

January 20, 1977 – January 20, 1981

|

49

| ||

January 20, 1981 – January 20, 1989

|

59

| ||

January 20, 1989 – January 20, 1993

|

63

| ||

January 20, 1993 – January 20, 2001

|

45

| ||

January 20, 2001 – January 20, 2009

|

54

| ||

January 20, 2009 to date

|

45

|

Capitals of the United States and Colonies of America

Philadelphia

|

Sept. 5, 1774 to Oct. 24, 1774

| |

Philadelphia

|

May 10, 1775 to Dec. 12, 1776

| |

Baltimore

|

Dec. 20, 1776 to Feb. 27, 1777

| |

Philadelphia

|

March 4, 1777 to Sept. 18, 1777

| |

Lancaster

|

September 27, 1777

| |

York

|

Sept. 30, 1777 to June 27, 1778

| |

Philadelphia

|

July 2, 1778 to June 21, 1783

| |

Princeton

|

June 30, 1783 to Nov. 4, 1783

| |

Annapolis

|

Nov. 26, 1783 to Aug. 19, 1784

| |

Trenton

|

Nov. 1, 1784 to Dec. 24, 1784

| |

New York City

|

Jan. 11, 1785 to Nov. 13, 1788

| |

New York City

|

October 6, 1788 to March 3,1789

| |

New York City

|

March 3,1789 to August 12, 1790

| |

Philadelphia

|

December 6,1790 to May 14, 1800

| |

Washington DC

|

November 17,1800 to Present

|

|

The author is pictured here holding the American Philosophical Society's Dunlap Declaration of Independence printed on vellum. |

We thank American Philosophical Society for allowing us to photograph and inspect the Original Draft and Dunlap Broadside of the Declaration of Independence. Please be sure to visit the APS web site by Clicking Here.

[i] Journals of the Continental Congress, Lee’s Resolution of Independence, July 2, 1776

[ii] Jefferson, Thomas Autobiography Draft dated January 6, 1821, The Thomas Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress

[iii] Adams, John. John Adams autobiography, part 1, "John Adams," through 1776. Part 1 is comprised of 53 sheets and 1 insertion; 210 pages total. Original manuscript from the Adams Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society. Page 2

[iv] Ibid

[v] Fitzpatrick, John C. The Spirit of the Revolution. Boston and New York: The Riverside Press Cambridge, 1924.

[vi] Journals of the Continental Congress, July 2, 1776

[vii] McKean, Thomas to Caesar A. Rodney, August 22, 1813, The Thomas Jefferson Papers Series 1. General Correspondence. 1651-1827

[viii] Adams, John. John Adams autobiography, part 1, "John Adams," through 1776. Part 1 is comprised of 53 sheets and 1 insertion; 210 pages total. Original manuscript from the Adams Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society. Sheets 40-41

[ix] Adams, John to Abigail Adams, July 3, 1776, Letters of Delegates to Congress: Volume 4 May 16, 1776 - August 15, 1776, Library of Congress

[x] Adams, John. Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams, 3 July 1776, "Had a Declaration..." . 3 pages. Original manuscript from the Adams Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.

[xi] Jefferson, Thomas Autobiography Draft dated January 6, 1821, The Thomas Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress

[xii] Adams, John. John Adams autobiography, part 1, "John Adams," through 1776, Original manuscript page 3

[xiii] Journals of the Continental Congress, Committee appointed to prepare the declaration, superintend and correct the press, July 4, 1776

[xiv] New York Provincial Congress, Resolution supporting the Declaration of Independence, July 9, 1776

[xv] Declaration of Independence Sotheby’s Sale, See: New York Times, For 1776 Copy of Declaration, A Record in an Online Auction, dated June 30, 2000

[xvi] The DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE, A Multitude of Amendments, Alterations and Additions, Appendix A - Extant copies of the 4 & 5 July 1776 Dunlap Broadside

[xvii] Declaration of Independence, German Printing, Pennsylvanisher Staatsbote, Henrich Millers: Philadelphia; July 9, 1776

[xviii] Journals of the Continental Congress, Official Copies of the Declaration of Independence, January 18, 1777.

[xix] Walsh, Michael J., "Contemporary Broadside Editions of the Declaration of Independence." Harvard Library Bulletin 3 (1949): 41.

[xx] Opt Cit, Engrossing The Unanimous Declaration Of The Thirteen United States of America, July 19, 1776

[xxi] Declaration of Independence, The Charters of Freedom, A New World is At Hand, The National Archives of the United States, 2005-2008, http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/declaration.html

[xxii] Ibid

[xxiii] Frederick W. True’s Semi-centennial history of the National Academy of Sciences, A History of the First Half-Century of the National Academy of Sciences 1863-1913, pp. 279-284.

[xxiv] The Daily National Intelligencer and Washington Advertiser, June 4, 1823

[xxv] Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States, 1823-1824 dated Wednesday, May 26, 1824.

[xxvi] William R. Coleman, "Counting the Stones: A Census of the Stone Facsimiles of the Declaration of Independence," Manuscripts 43 (Spring 1991): 103

[xxvii] Force, Peter; AMERICAN ARCHIVES: Containing A Documentary History Of The United States Of America Series 4, Six Volumes and Series 5,

[xxviii] Hancock, John to George Washington concerning the reading of the Declaration of Independence to the Revolutionary army, 4 July 1776, George Washington Papers, Library of Congress.

The Congressional Evolution of the United States of America

Continental Congress of the United Colonies Presidents

Continental Congress of the United States Presidents

July 2, 1776 to February 28, 1781

202-239-1774 | Office

202-239-0037 | FAX

Dr. Naomi and Stanley Yavneh Klos, Principals

Continental Congress of the United Colonies Presidents

Sept. 5, 1774 to July 1, 1776

September 5, 1774

|

October 22, 1774

| |

October 22, 1774

|

October 26, 1774

| |

May 20, 1775

|

May 24, 1775

| |